Measuring Progress

If someone asked you to drive from Kansas City to San Francisco in a car with no speedometer, no fuel gauge, no tachometer, no odometer, no oil pressure gauge, and no thermostat - you’d likely say no. These gauges are so fundamental to our understanding of how the car is performing, many of us cannot imagine driving without them. If we did, it would likely be a frustrating trip full of guesswork and worry - and all these gauges matter. Plenty of gas in the tank is useless if the engine is overheating. Good oil pressure is just as important as good gas mileage. Arriving safely and arriving without blowing a transmission are both important to your health and to your wallet.

In previous chapters, we talked about identifying priorities and setting goals in your organization (e.g., getting to San Francisco). Knowing the destination is critical. But the focus of this chapter is measuring progress along the way using a diverse suite of performance measures as gauges.

What Is a Performance Measure?

It’s the speedometer, the fuel gauge, the tachometer, the thermostat . . . Performance measures are what you look at to gauge how your program and/or organization are performing. They are descriptive, not diagnostic. They tell you how things are going (e.g., you’re out of gas). They don’t explain why (e.g., you missed the exit and didn’t fill up in time).

Types of Performance Measures

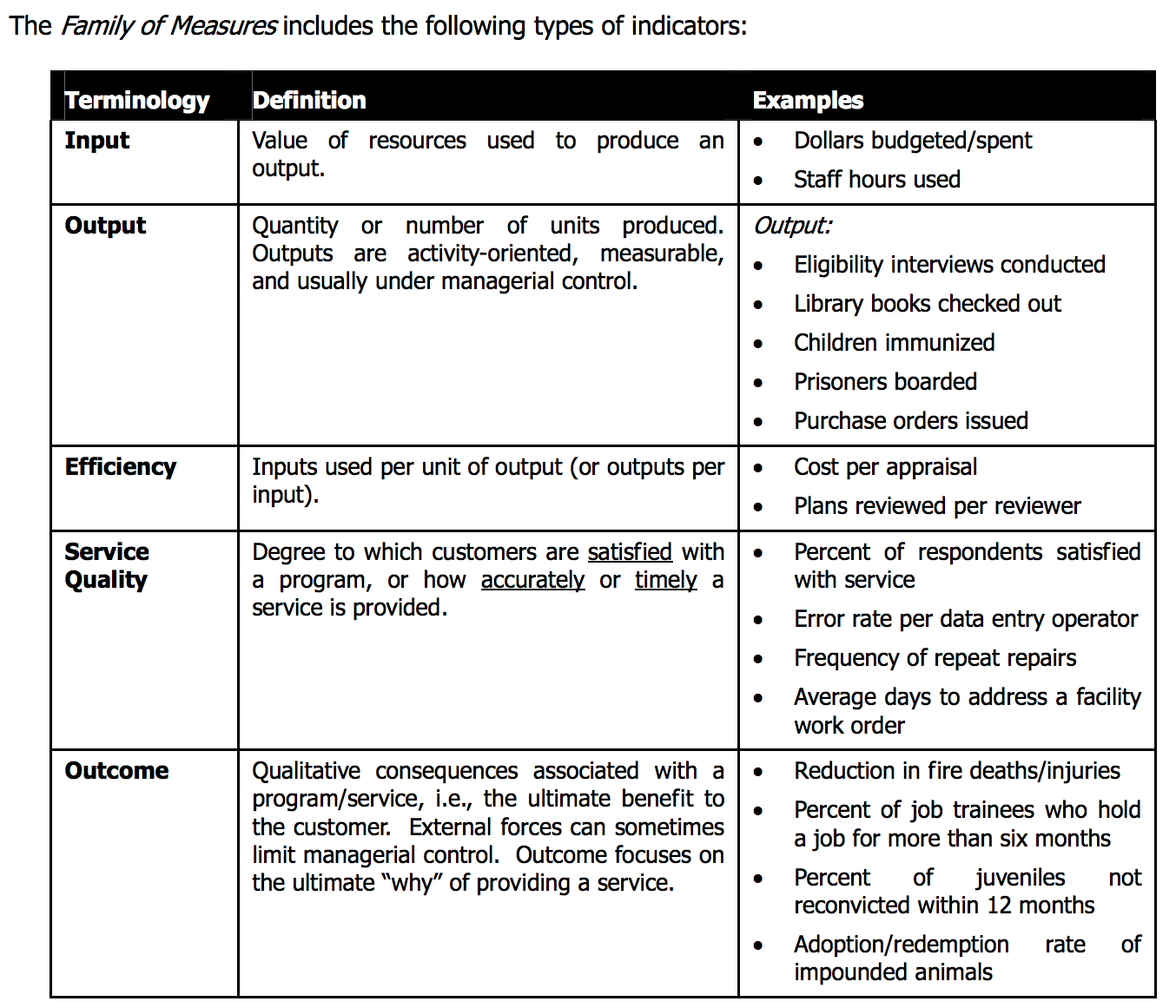

At GovEx, we encourage governments to use a diverse set of performance measures, sometimes referred to as a Family of Measures, because you’d never drive a car with an odometer but nothing else.

Why does GovEx encourage a diverse suite of measures?

Because outcomes matter (but so does the taxpayer), and GovEx does not believe in false choices. Many governments measure lots of outputs, not outcomes, so it is no surprise that performance management leaders are pushing their organizations to adopt an outcomes focus. While this is appropriate, measuring outcomes, inputs, and outputs are all important. Outcomes tell you whether the service achieved its ultimate purpose (e.g., did we get to San Francisco?). But the best way to get to San Francisco is to buy a private jet and fly there, an untenable plan when the taxpayer is footing the bill. Governments should look at ALL the gauges to understand performance toward strategic objectives. Getting there timely, safely, and cheaply are all considerations government managers must balance.

One of the best resources for understanding performance measurement, particularly in a strategic management context, is Fairfax County’s Advanced Performance Management Manual:

What Makes a Good Performance Measure?

The typical performance measurement guidance usually says performance measures should be S.M.A.R.T., a commonly used mnemonic acronym in performance management. It provides criteria for drafting strong goal statements. The concept originated in 1954 when Peter Drucker published a book about management by objectives. The idea is to ensure each goal statement fits all of the criteria in the acronym. The letters S and M usually mean specific and measurable, but the rest have numerous interpretations

- S = Specific, Strategic

- M = Measurable

- A = Achievable, Attainable, Action-Oriented, Agreed-upon, Aligned, Ambitious

- R = Relevant, Realistic, Resourced, Reasonable, Results-based

- T = Time-bound, Time-based, Time-limited, Timely, Time-sensitive

But the S.M.A.R.T. framework is not without controversy. Some take issue with the idea that strong performance measures must be “achievable.” Leaders, such as Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos, have made careers out of setting very difficult goals for their organizations, so the idea that progress measures must be “achievable” is at odds with the notion that organizations must stretch themselves to reach previously unattainable levels of performance.

Additional characteristics of strong performance measures outside the S.M.A.R.T. framework are listed below.

- Easy to understand: measures should be intuitive and easily digested by residents and employees without much explanation, because if they can’t understand it, then how will you ever be able to explain the results?

- Incentivize the right behavior: performance management is littered with examples of performance measures incentivizing the wrong behaviors, like the scandal at the Veteran’s Health Administration in 2014 when veterans were kept waiting on unofficial lists to keep wait times appearing favorable. When deciding on the right measure, make sure hitting those targets doesn’t incentivize wrong-headed behavior at odds with your city’s overarching goals to serve residents well.

- Visible/transparent to those involved: How you are measuring performance should be plainly visible to everyone involved and be held accountable to those measures. Such transparency helps everyone keep their eyes on the ball and understand their contribution to the overarching performance of the organization.

- Less is more: Measuring everything at a department level is no better than measuring nothing, because no one can pay attention to every aspect of an operation. Stay focused, narrow the list of what you are focusing on improving, and you’ll get further faster.

Common Mistakes

- Too many measures: Organizations that measure everything, end up understanding nothing because insights get diluted in the noise

- Unaligned to strategic priorities: Organizations that cannot link performance gauges to the final destination are far less likely to arrive at their destination on time, intact, and on budget

- Nothing under the hood: Many organizations write down measures without an underlying data collection, calculation, and reporting methodology. These are vital if the measures are ever going to be real.

- Unrealistic: Sometimes the most well-intentioned measures are simply outside the reality of data collection. This is very common with outcome measures, which sound great in theory, but are much harder to capture in practice.