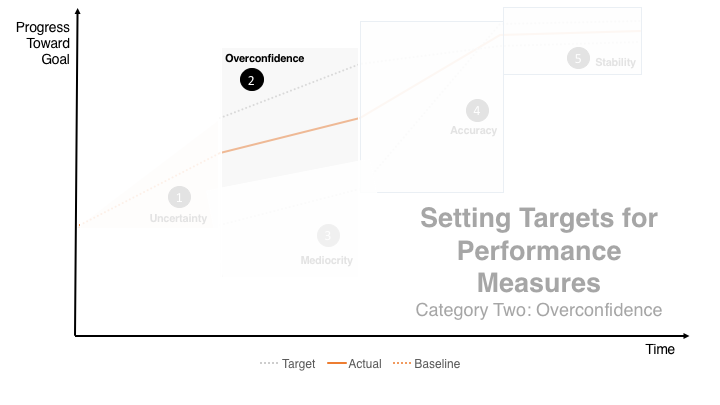

Category Two: Overconfidence

Overconfidence occurs when targets are unrealistic and unattainable based on all available evidence. There is no evidence the government has ever performed at the target level, and no evidence it can reach the target. It is pure optimism and/or sheer political will. This is most common when a government is trying to take an aggressive position to inspire higher performance, regardless of the evidence.

Why does overconfidence matter?

In 1962, President Kennedy famously said “We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the moon and do other things in this decade, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.” Seven years later, Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the Sea of Tranquility. For leaders like Kennedy, setting a bold goal to harness “the best of best of our energies and skills” is laudable. History is made by leaders like these. However, overconfident goals are the Hail-Mary passes of performance management, and should be reserved for rare occasions when a leader is willing to make “all-in” investments and stake significant political capital on their achievement. For the regular business of government (e.g., the non moon-landing stuff), setting the bar unreasonably high can have unintended negative consequences on morale and culture. In an effort to inspire improvement, an overconfident manager or leader can unintentionally create a Darwinian culture where some thrive on the bold target and others feel threatened by unfair expectations. In addition, an unreasonable target is rarely met (or takes a long time to achieve), guaranteeing an “I told you so” showdown and eroding buy-in for future initiatives. In performance management, it is great to be confident. Just base the confidence on evidence.

Signs of overconfidence:

- There is no internal consensus about the validity of the target – in fact some people are not even sure where the target came from.

- The target is set far beyond a reasonable range based on past performance and baseline data.

- The target was set by someone other than the subject matter expert.

Figure 3

What to do with overconfidence?

- Understand it. There may or may not be a reason someone is setting targets (and expectations) so unattainably high. They might not know the baseline historical data well. They might be relying on performance targets they have seen in other jurisdictions. Or they might be trying to inspire aggressive change. Many executives set an impossible target hoping the program will get halfway there - further than they would have gone without it. Once there is an understanding of the reason for overconfidence, it can be corrected (or let go).

- Correct it. Correcting for overconfidence is easy, because the data is available. For the average program manager, there are four quick things to make the case for a more reasonable target that still drives performance improvement:

- Adjust the timelines. If the target setter is unwilling to change the target, consider adjusting the timeline for achieveing it.

- Let it go. If leadership wants to set impossibly high expectations, there are worse problems to have.

What not to do with overconfidence?

- Do not be defensive. Aggressive targets are usually set by aggressive leaders who want aggressive improvement, which is often intimidating. People are hesitant to challenge an aggressive leader’s assumptions. They do not want to disappoint or seem like a naysayer. Instead of being defensive, be inspired. When working for such a champion of change, the main task is to demonstrate competent analysis he/she can rely on to calibrate his/her high expectations.

- Do not assume they know better. Many targets are set in an information vacuum, so do not assume leaders have seen the baseline data and decided to ignore it. Create an opportunity to show them the baseline and how it relates to existing targets.

- Do not overcorrect. Pendulums are known for swinging back in the opposite direction, especially during a change in leadership. When guiding a leadership team from overconfidence toward reality, do not steer the team toward mediocrity.